The ironic state of dependency management in Python (I)

There is no doubt that if there is one programming language that has gained respect and admiration in the last decade, (among others), it would be Python

Artificial intelligence? Python. Web applications? Python. Learning to program? Python. Learning Python? Python. Few tasks escape this dynamic language that began displacing the king of scripting in the 1990s, Perl.

Created by Dutchman Guido Van Rossum in the late 80s, it saw its first version in 91 and since then has been gaining positions in the various annual rankings in which programming languages are positioned in various criteria.

It is worth asking if there is something that this language does not do well and the answer would be: Of course. One of them, quite repeated in the community, is the management system of packages, dependencies, and versions of the interpreter when you get into work with a project.

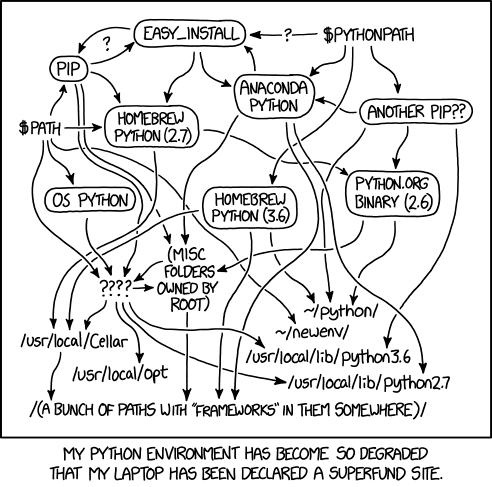

Even the great creator of the XKCD comic, Randall Munroe, dedicated one of his vignettes to this problem:

"It worked on my computer"

Engineers like reproducible systems with no hindrances. Which means you design, develop, test, and when everything is ready, theory says that you should deploy and run it without problems. Practice, however, teaches us that the result is quite the opposite.

Therefore, one of the purposes of containers or virtualization is to try to blur the line between the two universes in constant discrepancy: the development environment and the production environment.

◾If we remember, when Java was announced back in '96 one of the slogans was: Write Once, Run Everywhere. And it was all thanks to the Java Virtual Machine, the JVM, which relieved programmers of two burdens:

1. manual memory management thanks to a garbage collector and

2. the abstraction layer over the operating system that hosted the environment.

While not perfect, the JVM did a very good job in that regard.

Regarding the Python ecosystem, it is cross-platform in the sense that the Python interpreter is available for multiple systems, and you also abstract (with identical limitations to Java) from the underlying platform.

So far so good, except that on an operating system the version of Python installed may not be the same as the one on which the application was developed. What's more, a few years ago the Python world split in two, like a schism, with the advent of version 3 of the language.

- On one side were those who were reluctant to change from the then popular Python 2.7.

- On the other side were the group of adventurers who were entering the then wasteland that was Python 3 (also known as Python 3000); we say wasteland because the ecosystem of libraries was still extremely incipient in terms of versions for Python 3.

As a result, we are faced with the problem that the project we are developing is tied to a specific version and any other target system will not support it.

How do we solve it?

We obviously have to install a new interpreter with the required version and make it coexist with the original one. There are projects that allow us to do exactly that, install as many Python interpreters as we want with a single and discreet drawback (that you can even automate): You must take care of selecting the right version before launching the project or any feature you need for testing or continuous integration.

Pyenv, an open-source and available for UNIX systems (there is a fork for Windows) is a project that installs a command line utility to manage Python's. It is simple to use once you understand it. It is simple to use once you understand the concepts with which it works.

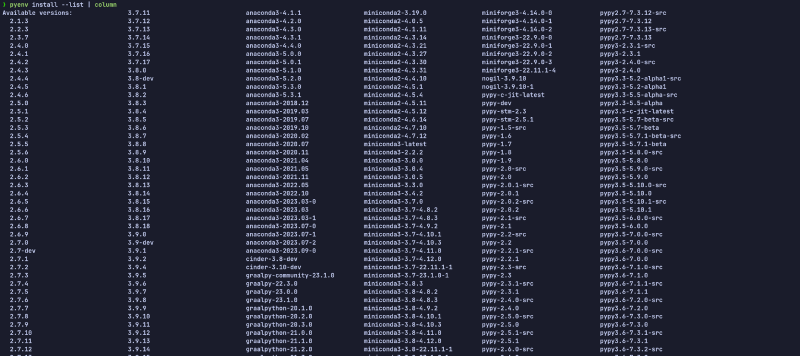

First of all, it installs the interpreter of your choice. The list is endless. You can install from deprecated versions (mostly used for regression testing on still supported libraries), alternative interpreters (Pypy, Jython...) and popular distributions, such as Anaconda.

Once we have the interpreter (or the ones we want) installed, it will not be active yet. Here we have a variety of options to make it flexible and adapt it to our needs. First, we can choose to activate an interpreter globally, affecting the whole system. Any new shell we create will have that interpreter as its main interpreter and any process that calls Python will also have that interpreter as its target.

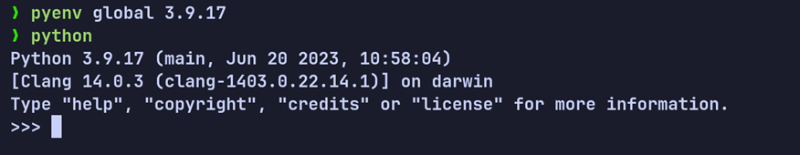

Say, for example, that I want the operating system in general to recognize Python 3.9.17 as the interpreter to use. The command is simple: pyenv global 3.9.17

With that command all "python" will be 3.9.17.

But, of course, affecting the whole system in general is something that can produce undesirable side effects. We want to reduce it to the level of the folder we are working on. That is to say, that all the shell sessions that we open in that folder have that interpreter as reference.

It is simple, instead of global, we will use local. This will create a file called .python-version which only contains the name with which pyenv will alter the paths of the environment so that when we type python and we are in that folder, the interpreter will be the appropriate one. Magic.

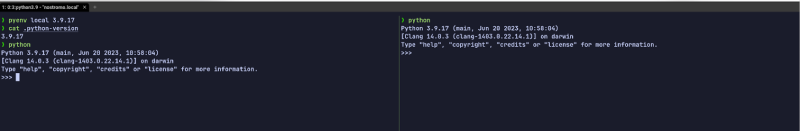

In the screenshot we can see it illustrated. We tell pyenv that version 3.9.17 will be used in that directory and any shell we open there will be tied to that interpreter.

Even more flexible. Let's suppose that inside the directory we want to do a small test with another version of Python. What can we do?

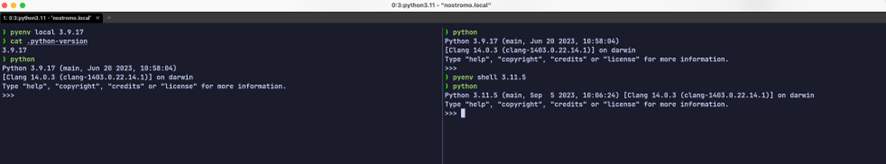

pyenv shell 3.11.5

That alters only that shell, which will now point to Python version 3.11.5. No other session will be altered, only what we run there. Let's look at the screenshot:

This is Hollywood. Once we finish our tests, we do a pyenv shell --unset and go back to where we were.

With this, we practically solve the problem of the interpreters. We can have as many as we want.

—CONTINUING THIS SERIES

Hybrid Cloud

Hybrid Cloud Cyber Security & NaaS

Cyber Security & NaaS AI & Data

AI & Data IoT & Connectivity

IoT & Connectivity Business Applications

Business Applications Intelligent Workplace

Intelligent Workplace Consulting & Professional Services

Consulting & Professional Services Small Medium Enterprise

Small Medium Enterprise Health and Social Care

Health and Social Care Industry

Industry Retail

Retail Tourism and Leisure

Tourism and Leisure Transport & Logistics

Transport & Logistics Energy & Utilities

Energy & Utilities Banking and Finance

Banking and Finance Smart Cities

Smart Cities Public Sector

Public Sector