Dealing with password fatigue

Holidays are over and we're back at work. We switch on the computer, open the email manager and... Oh, the password! It is expired. You send a request to IT to have it reset and you have to wait.

A few floors down or a building down the street or perhaps on the other side of the Atlantic, someone from the IT department opens the ticket manager, looks at the screen, crunches his fingers and takes a sip of the coffee that will inevitably cool down before he can drink it again. He sighs, shifts his chair, and settles a back ready for a couple of contractures to land 500 password reset tickets later.

Is it a good security measure for a password to expire like a carton of milk?

That's what Bret Arsenault (Microsoft's CISO) asked himself when he abolished the company's internal policy requiring passwords to be changed every 71 days.

Arsenault is critical of passwords. What's more, we fall short. It is not really a question of whether or not password refreshing is a productive security measure, but rather suggests that the very use of passwords is inadequate, unreliable, and an outdated model.

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/bret-arsenault_in-the-future-there-will-be-no-passwordsbecause-activity-6993973391414210560-CfQx

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/bret-arsenault_in-the-future-there-will-be-no-passwordsbecause-activity-6993973391414210560-CfQx

Of course, withdrawing such a measure seems counterproductive. A leap of faith. An inch gained by flexibility at the cost of sacrificing security in this eternal tug of war between the two irreconcilable extremes. Initially, it's scary to think that an attacker could get hold of a password and gain access to the organisation indefinitely.

It's even more complicated. You have to be optimistic to think that an attacker is going to keep a credential indefinitely and only move from that point, like clocking in every day with that same card. In fact, the equivalent is getting an employee card and pretending that we can go through the turnstile for months without anyone noticing an intrusion. Wrong.

That is indeed the point at issue: does having something as weak as a password give us a free hand to do whatever we want? Do we have to trust that identity? Not at all. That's why we have security guards, video surveillance cameras, etc. Or are we going to wait until that card is renewed or the employee reports the theft before we realise that something is wrong?

The "zero trust" model is based on the assumption that things go wrong until the opposite is verified.

It is the same principle that has to be transferred to the network and already exists: the "zero trust" model. This in turn is based on the assumption that things go wrong until the opposite is verified. Just the reverse of "nothing has to go wrong unless we detect a divergence in the system".

Three types of factors and why the password is fuzzy in this regard

You may have read this more than once: Authentication factors are based on three classes in an abstract way: what you know, what you own and what you are. The first is a secret, the second is an object, and the third is you (biometrics, of course).

Where would you put the password: in your memory (you know it) or in your password manager (you own it)? If it's in your memory, I bet it's weak. Moreover, I dare you, I dare you twice that I am able to figure it out sooner or later. Memory is brittle and unless you are a genius at memorising long and complex strings of characters, your password is weak for sure.

As we can see, the password is a fuzzy factor that can go from something you know (you memorise it) to something you own (the password manager). Like the old-fashioned "security questions", it is a counterproductive measure that is fortunately becoming less and less common. There is no worse security measure than one that we trust but ignore that it is useless.

It must be conceded that, given that a well-operated password manager pivots passwords towards an "object you have" and allows us, at least, to create secure passwords and, as an essential measure, not to share them between different sites or domains.

Why are passwords so bad

Their bad reputation is no coincidence but has been built on facts. What are the famous, headline-grabbing leaks mainly about: biometric data or OTP device seeds? They are mostly about personal data and passwords (well, hashes, for another article).

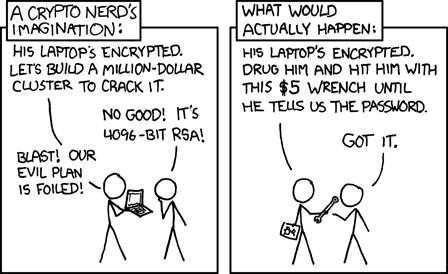

Passwords are also stored on disk or in memory. Within the reach of any malicious process (https://github.com/AlessandroZ/LaZagne, a wonder in the world of computers), not to mention how relatively easy it is for someone to "give you" the password with a few drops of social engineering. "Hi, I'm the support technician...".

On top of that, if we refresh passwords there are users whose pattern is based on changing a couple of digits sequentially at most: passwordA2021, passwordA2022... That's not security, it's a false security measure. It adds nothing.

As we have already mentioned, what if that password is also shared on several sites? It is possible that it is exfiltrated on a totally unrelated site and because it is shared for convenience, wham, the password has already fallen into the hands of someone who should not have it.

Some employees even log on to sites using their business email address, which is totally inappropriate, both from a security and reputational point of view, and ethically reprehensible, especially in the case of a public leak.

So?

Neither unique passwords nor passwords that are difficult to remember. We have already touched on this in this article: mandatory second authentication factor and an architecture that provides the minimum trust and confidence in the identity.

Changing passwords only leads to increased user frustration and wastes valuable hours for the IT team. The second factor (and why not even the third factor) gives us an additional safety net; though of course, it is not a panacea either.

Rather than letting someone through the security check and then ignoring their actions, mistrust is the most important tool here. If someone must enter your organisation to perform a particular task at a particular time, what you have to make sure is that they are the right person, that they are on the right path and do what they have to do in the right window of time, and that they do it with the necessary permissions and resources and nothing else. Instead, it is a security event to which we must pay attention.

As it is said,

"You trust, but then you check”.

Imagen: Freepik.

Hybrid Cloud

Hybrid Cloud Cyber Security & NaaS

Cyber Security & NaaS AI & Data

AI & Data IoT & Connectivity

IoT & Connectivity Business Applications

Business Applications Intelligent Workplace

Intelligent Workplace Consulting & Professional Services

Consulting & Professional Services Small Medium Enterprise

Small Medium Enterprise Health and Social Care

Health and Social Care Industry

Industry Retail

Retail Tourism and Leisure

Tourism and Leisure Transport & Logistics

Transport & Logistics Energy & Utilities

Energy & Utilities Banking and Finance

Banking and Finance Smart Cities

Smart Cities Public Sector

Public Sector-1.jpg)