Digital wallets: Maximum usability, maximum security?

Introduction

Most of us are now accustomed to digital wallets on our mobile devices. We rarely carry physical bank cards with us in our daily lives and travels, at least in my case.

If you’re also a heavy mobile digital wallet user, the research presented in this scientific article will interest you. We’ll analyze the vulnerabilities identified in the study, their impact, and explore the researchers’ proposed solutions, drawing conclusions along the way.

Digital wallets

To start, let’s define digital wallets and their utility. They represent a new form of payment technology, providing a secure and convenient way to make contactless payments through smart devices like mobile phones. The most well-known applications include Gpay (Android), ApplePay (iOS), PayPal, among others.

Through the app, we can incorporate our bank cards, authorize this new form of payment, and from then on, carry the card on our mobile device, enabling us to make payments or even withdraw cash from ATMs using the NFC technology embedded in our mobile terminals.

This undoubtedly enhances user convenience and usability since, nowadays, the mobile phone is the first item we ensure we have before leaving home. With digital wallets and the digitalization of national identification systems (such as the driver’s license or the national ID), it’s almost the only thing needed, along with our keys.

However, the intriguing research we reference raises the question of whether the balance between usability, which is undeniable, and security is adequate. This poses a series of important questions:

- Authentication: How effective are the security measures imposed by the bank and the digital wallet application when adding a card to the wallet

- Authorization: Can an attacker pay using a stolen card through a digital wallet?

- Authorization: Are the victim’s actions, i.e., (a) blocking the card and (b) reporting the card as stolen and requesting a replacement, sufficient to prevent malicious payments with stolen cards?

- Access control: How can an attacker bypass access control restrictions on stolen cards?

As a result of digital wallet payments, a new player enters the scenario: the digital wallet application and its integration with smart devices, as well as the trust that banks place in them. This new digital payment ecosystem, which allows for decentralized delegation of authority, is precisely what makes it susceptible to various attacks.

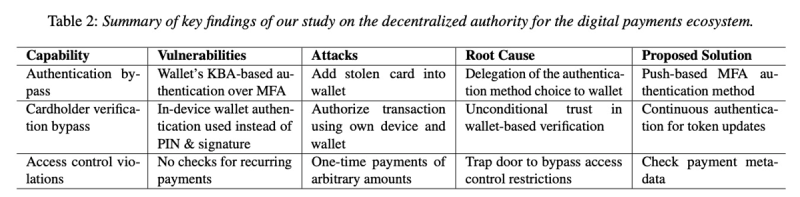

Summary table of findings from the research presented last week at the USENIX Security Conference

Summary table of findings from the research presented last week at the USENIX Security Conference

Next, we’ll delve into the main weaknesses and vulnerabilities uncovered by the researchers, as summarized in the previous table.

There is too much reliance on digital wallets by banks without checking ownership of cards.

Authentication: the process of adding cards to the digital wallet

According to the research, the main issue lies in the fact that some banks do not enforce multi-factor authentication (MFA) and allow users to add a card to a wallet using knowledge-based authentication, a procedure for which attackers can exploit leaked or exposed personal data of the victim to impersonate the legitimate cardholder when adding the card to the digital wallet.

✅ For example, an attacker could add a stolen card to their digital wallet using the victim’s postal code, billing address, or other personal details that can be easily discovered online or included with the stolen card package by a dark web vendor.

In multiple cases, the wallet user can choose the authentication mechanism to use from the options available in agreements between the bank and the digital wallet app. However, in reality, the most secure option should always be chosen from among those available.

Authorization: at time of payment

At the time of payment, it’s common, at least in my experience, to use biometric parameters to approve payments on a point-of-sale terminal, which, by design, isn’t entirely correct.

It's strong authentication from a technical standpoint, but it doesn’t demonstrate what is required when using a physical card (the possession of the card and our legitimate use of it, such as with a classic PIN) but rather the possession of a smart terminal and a card available in a digital wallet, which isn’t the same.

Numerous banks allow the use of the same card on multiple terminals. This is useful, for example, for users who use more than one terminal or for parents who allow certain bank cards to be used by their children.

⚠️ However, this facilitates attackers' work if they obtain a stolen card, exploiting the time between the theft and notification of the loss. If they manage to associate the card with their digital wallet, they can then use it for future payments simply by owning a terminal, something they logically meet.

Authorization: what happens to stolen cards?

An even more surprising finding of the research is the lack of rigor in critical processes, such as the notification of card blocking or theft by the victim.

The researchers found that even if the victim detects that their card has been stolen, blocking and replacing the card doesn’t work 100%, and the attacker can still use the card previously added to their wallet without requiring (re)authentication.

The main issue here is that banks assign digital wallets a PANid (Primary Account Number Identification) and a payment token when adding a card.

When a card is replaced, some banks issue a new PANid and a payment token to all wallets where the card was added, assuming all wallets are controlled by the legitimate owner. These tokens allow attackers to continue using their digital wallets, now authorized to make purchases with the reissued card.

⚠️ This is serious, a clear example of excessive trust between the bank and the digital wallet: assuming that the cards in digital wallets are legitimate, they associate the new card identifier with the same payment token already present with the old card, allowing for fraudulent use even if the card has been reported to the bank by the victim.

Access control: one-time vs. recurring payments

The last point highlighted in the research is the difference between bank policies on individual payments and recurring payments.

Banks generally allow recurring payments even on blocked cards to minimize the impact on customers’ services, such as a Netflix subscription or similar.

However, it’s the online store that exclusively decides and labels whether a payment is marked as recurring or one-time.

The verification of the recurring nature of a payment leaves much to be desired, as the researchers empirically discovered, allowing for payment of services that logically should not be recurrent due to the characteristics of the service itself, such as purchasing a gift card or renting a car, nor due to the amount or frequency of payments.

This lack of validation in recurring payments can enable an attacker to use a stolen card for payments that would be blocked if they were labeled as one-time payments, with the complicity of a fraudulent business, or simply by seeking out merchants that default to such payment labels.

Mitigations

Let’s review the measures the authors propose to address deficiencies identified in their research.

- Authentication: This can be easily prevented by enforcing MFA and sending an SMS or push notification to the victim’s phone number, a challenge that few attackers could overcome, at least not passively.

- Authorization: Once the digital wallet is authenticated and a payment token is issued, the bank uses the token indefinitely, which never expires. This establishes unconditional trust in the wallet, which neither expires nor changes, even during critical events such as card loss, device loss, and card deletion. Banks should adopt a continuous authentication protocol, re-authenticate the digital wallet, and refresh the payment token periodically, at a minimum after critical events such as card loss.

- Recurring Payments: Today, the bank relies on the transaction type label assigned by the merchant to decide on the authorization mechanism. The bank should evaluate the transaction metadata and validate it (e.g., time, frequency, and type of service/product) with the transaction history information to assess whether the transaction is of a certain type or not.

The mobile payment system needs to be more secure to prevent fraud and abuse.

Conclusions

This study is based on American banking entities but is likely applicable to other banking entities worldwide.

The trust banks place in digital wallets is currently excessive, seeking a smooth interaction with the end-user —a naturally good thing— but critical processes such as adding a card to a wallet should be carefully reviewed and fortified to ensure the legitimate ownership of the card by the user and to periodically verify that this continues to be the case over time.

Biometrics cannot guarantee strong authentication for digital wallet payments.

The use of biometrics to make a payment gives the appearance of strong authentication, but in the case of digital wallets, it doesn’t verify the essential aspect of a payment, which is that a user legitimately possesses a terminal, not something actually related to the card we’re using. This design flaw is a security gap through which attackers can slip… It seems there’s a need to significantly improve the “abuse cases” in the secure development cycle of digital wallet applications and their integration with banking entities.

As they say in Galicia,

Friends, yes, but the cow is worth what it’s worth.

Hybrid Cloud

Hybrid Cloud Cyber Security & NaaS

Cyber Security & NaaS AI & Data

AI & Data IoT & Connectivity

IoT & Connectivity Business Applications

Business Applications Intelligent Workplace

Intelligent Workplace Consulting & Professional Services

Consulting & Professional Services Small Medium Enterprise

Small Medium Enterprise Health and Social Care

Health and Social Care Industry

Industry Retail

Retail Tourism and Leisure

Tourism and Leisure Transport & Logistics

Transport & Logistics Energy & Utilities

Energy & Utilities Banking and Finance

Banking and Finance Smart Cities

Smart Cities Public Sector

Public Sector