Linux and the vulnerability paradox: More reports, more security?

We recently published our 2024 H2 Security Status Report, an in-depth analysis of the key threats, vulnerabilities, and trends in cybersecurity during the second half of last year.

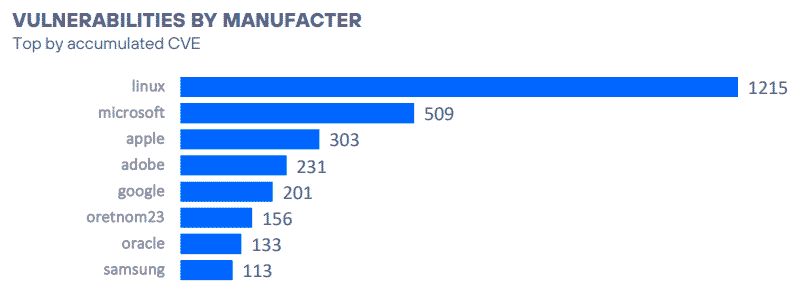

In the section focusing on critical vulnerabilities identified during this period, we observed a significant increase in the number of reported and fixed vulnerabilities associated with Linux. While previous semesters recorded around 200 vulnerabilities, the second half of 2024 saw 1,215 documented cases. This represents an increase of over 500%, a spike that does not have a simple or singular explanation, raising questions about its causes and implications.

Source: State of Security Report 2024 H2.

Source: State of Security Report 2024 H2.

At first glance, this might seem like a sign of greater insecurity, but the reality is far more complex. To better understand this phenomenon, we have compiled several explanations that might clarify the reasons behind the surge in reported vulnerabilities.

■ CVE (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) are unique identifiers assigned to known security vulnerabilities in software and systems. Their purpose is to standardize the identification and documentation of security flaws, making it easier to track and mitigate them to manage threats, implementing corrective measures, and improving system security more efficiently.

1. The Linux kernel as a CVE Numbering Authority (CNA)

One key factor contributing to this increase is that in 2024, the Linux kernel was accredited as a CVE Numbering Authority (CNA) by the CVE Program. This designation allows the kernel team to assign CVE identifiers to vulnerabilities they discover and fix. As a result, vulnerability documentation has become more detailed and frequent, contributing to the higher number of reported CVEs in the second half of 2024.

This change has enhanced transparency in the vulnerability disclosure process and allowed for better organization in kernel security management. Although the number of reported CVEs has increased, this does not necessarily indicate a rise in system insecurity. On the contrary, it may reflect an improvement in resolved issues documentation and visibility. With easier CVE management, even minor flaws are now reported and classified.

2. Open-source transparency

Unlike proprietary systems, Linux operates under an open-source model, meaning anyone can examine the code, search for flaws, and report them. This level of transparency ensures vulnerabilities are documented publicly and accessible.

This means that assessing security solely based on the number of recorded vulnerabilities can be misleading. A system with fewer reports is not necessarily more secure—it may simply be less audited or less transparent in disclosing flaws.

3. Security as an active process

Linux benefits from a global community of developers and security researchers who continuously work to find and fix vulnerabilities. The level of scrutiny may be more rigorous than in other systems, where security audits rely solely on the teams that develop them.

A system with an active community constantly searching for and correcting errors is more secure in the long run. In this sense, the increase in reported CVEs should not be seen as a sign of weakness, but rather as an indication of constant vigilance, ensuring that problems are resolved before they can be exploited.

4. Linux’s omnipresence: More code, more reports

Linux is not a rigid OS confined to a single type of use. It is ubiquitous, running on enterprise servers, embedded systems, IoT devices, supercomputers, and smartphones. This diversity of applications results in an immense codebase with multiple layers of functionality, spanning the kernel, modules, and drivers.

Each new use case introduces entirely different security scenarios requiring review. The broader the Linux ecosystem, the more potential vulnerabilities emerge due to its scale and varied implementations. However, this does not mean Linux is inherently less secure—it is a system that evolves to adapt to these environments.

5. It’s not just about finding flaws—it’s about fixing them

The fact that the Linux ecosystem has fixed over 1,200 vulnerabilities in six months could be seen as a positive indicator. In the software industry, what is truly concerning is not how many vulnerabilities are found, but how long they remain unpatched.

Linux’s open development model and frequent updates enable rapid bug fixes. A high number of reported vulnerabilities should be analyzed in the context of how quickly they are addressed, rather than just the raw figures.

6. The definition of ‘Linux’ and how vulnerabilities are counted

Another crucial factor is how CVEs are counted in Linux. The ‘Linux’ category in vulnerability reports does not only include the core kernel, but also a wide range of modules, drivers, and peripheral components. Each of these elements can generate individual CVEs, artificially inflating the total count.

For example, if a specific driver receives multiple vulnerability reports, each one can be counted as a separate CVE, even if its actual impact on overall system security is minimal. This level of granularity in reporting increases the numbers but does not necessarily indicate a more insecure kernel.

Conclusion

Security perceptions based solely on the number of reported vulnerabilities can be misleading. Linux's surge in CVEs may be attributed to its open and highly audited nature. This is where flaws are found, documented, and fixed swiftly and transparently. Additionally, it is likely a reflection of Linux’s accreditation as a CVE Numbering Authority, increasing visibility and responsibility in vulnerability management.

Security of any system is not just about the number of vulnerabilities discovered, but also about how they are managed and what measures are taken to mitigate risks.

Ultimately, data interpretation must always consider the context—not just the raw count of reported vulnerabilities, but also their severity, resolution time, and development model. Assessing a system's security requires a broader analysis that transcends beyond the mere accumulation of vulnerability reports.

— BY David García, Sergio de los Santos, NACHO PALOU —

Hybrid Cloud

Hybrid Cloud Cyber Security & NaaS

Cyber Security & NaaS AI & Data

AI & Data IoT & Connectivity

IoT & Connectivity Business Applications

Business Applications Intelligent Workplace

Intelligent Workplace Consulting & Professional Services

Consulting & Professional Services Small Medium Enterprise

Small Medium Enterprise Health and Social Care

Health and Social Care Industry

Industry Retail

Retail Tourism and Leisure

Tourism and Leisure Transport & Logistics

Transport & Logistics Energy & Utilities

Energy & Utilities Banking and Finance

Banking and Finance Smart Cities

Smart Cities Public Sector

Public Sector