Quantum Machine Learning: the next revolution in AI?

AI and Machine Learning were, for decades, the ‘ugly ducklings’ of computer science due to hardware limitations, which kept methods like neural networks confined to academic books and theoretical papers. There was no real guarantee they would actually work, yet today neural networks run the world, even if we still don’t fully understand them.

Applications like classifiers, recommendation systems, computer vision, or LLMs (ChatGPT and its peers) are now part of our daily lives. There are quite a few parallels with quantum computing, the eternal promise that is gradually approaching a practical horizon; uncertain, yes, but already attracting billions in investment.

So let’s combine the two most hyped fields today: AI and quantum computing. What could possibly go wrong?

The playing field: classical vs quantum

First, a quick disclaimer: we’ll focus on Quantum Machine Learning (QML), which assumes at least a basic understanding of quantum computing. To get up to speed (and see Telefónica Tech’s role in this space), check out our previous blog posts series.

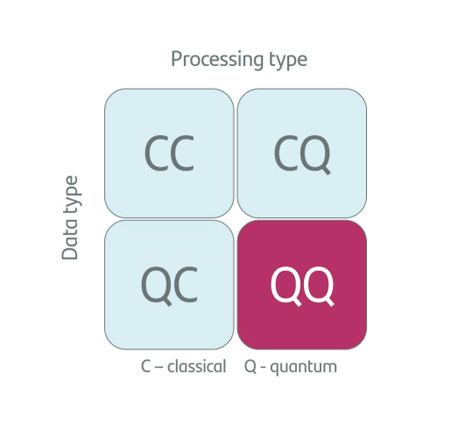

If we’re talking about AI and Machine Learning, we first need to define what we’re cooking (the data) and what oven we’re using (the processing). This gives rise to four core paradigms:

- CC (Classical data, classical processing): traditional ML. Logistic regression, facial recognition networks, or ChatGPT.

- QC (Quantum data, classical processing): classical ML used to analyze quantum states from experiments or detectors, applied mainly in basic science.

- CQ (Classical data, quantum processing): The current Holy Grail: using classical data (images, text, etc.) on a quantum computer to harness its vastly superior computational power.

- QQ (Quantum data, quantum processing): The pure vision—Feynman’s dream. A quantum computer learning from quantum nature (e.g., molecular simulation). Right now, more science fiction than Star Wars.

If we’re talking about AI and machine learning, we need to define what we’re cooking and in what oven.

Let’s focus on that ‘holy grail’: using a quantum computer to make machine learning faster and more accurate. Training complex neural networks is essentially an optimization problem: we’re trying to find the lowest point on a mountain range we’ve never seen before (the loss function). Which direction do we move in? How fast? How do we know the minimum we’ve found is the lowest possible? Should the landscape around us influence our next move?

Training a large neural network is a very hard problem, so any extra computing power is welcome (hence the Nvidia GPU craze and megadata centers). In today’s quantum computing (known as NISQ, or Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum), we don’t have perfect machines. Due to the delicate nature of quantum chips, they produce many errors that are hard to correct. That’s why the dominant approach is the use of Variational Quantum Circuits (VQC).

The challenge of encoding classical data into quantum systems

It works as a hybrid system, where the (classical) CPU tells the (quantum) QPU: "Try rotating your qubits with these parameters" (something you can't do with traditional bits). The QPU runs the circuit and measures the outcome. The CPU checks the result and says: "Slight improvement, now tweak the parameters like this instead". And so on, iteratively, until the best possible outcome is reached.

A quantum computer doesn’t understand JPEGs or Excel files.

It’s essentially the same kind of optimization problem as before. The theoretical advantage lies in the fact that the ‘mountain map’ in Hilbert space (the mathematical space qubits live in) is vastly richer and more dimensional than classical space. This, in theory, allows shortcuts to the global minimum that a classical computer would never see. So, is it that simple? If someone handed us a quantum computer, would it be plug-and-play?

Unfortunately, no. A quantum computer doesn’t understand JPEGs or Excel. Its language is based on wave amplitudes and spin states. Encoding is the process of translating classical data (your usual x values) into a quantum state. But if you have a dataset with one million entries, and it takes a million steps just to load them into the quantum computer, you’ve already lost your exponential advantage before even starting. It’s like having a Ferrari, but having to push it by hand to the highway.

■ There are encoding techniques like amplitude, basis, or phase encoding, but preparing these states in real-world problems is extremely expensive and requires very deep circuits that, as of today, generate too much noise. Without a working QRAM (quantum RAM), which doesn't physically exist yet, this remains the first bottleneck, but certainly not the last.

In search of the missing algorithm

The legendary Shor’s algorithm from 1995 mathematically proved that a quantum computer can factor numbers exponentially faster than any known classical algorithm, breaking RSA encryption (based on factoring huge numbers), which secures most of our digital information. While today's best supercomputers would need billions of years to crack it, a practical quantum computer with thousands of qubits could do it in a matter of hours.

Machine Learning hasn’t had its 'Shor moment' yet. There’s no definitive proof that a QML algorithm offers a generalizable exponential advantage for classical data problems. There are algorithms like HHL to solve linear equation systems (a foundation of many ML techniques). It’s exponentially fast, but comes with so many input/output constraints that it’s nearly unusable in practice.

Machine Learning hasn’t had its 'Shor moment' yet.

Hope lies not in brute force, but in the quantum kernel trick (the quantum version of a classical ML technique used in Support Vector Machines). Quantum computers can naturally compute distances between data in infinitely dimensional spaces. If we can show that certain patterns are only separable in that space, we will have achieved real-world advantage.

Technical and theoretical challenges in Quantum Machine Learning

Today, we’re still in the ‘scientific playground’ phase. Maybe one day we’ll train an LLM far more efficiently with fewer parameters using quantum computing. For now, so-called quantum-inspired algorithms have already shown that techniques from quantum mechanics and complex systems like tensor networks can compress neural network models, from CNNs to LLMs, proving that quantum and AI are destined to converge.

Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) exist and run on simulators and small chips. But they face a problem known as the barren plateau. A similar issue once plagued classical ML under the name vanishing gradient. Think back to our mountain map: imagine you’re in a shallow valley. The slope is gentle and the terrain bumpy, you struggle to tell which direction leads down, but with patience and precise steps, you’ll find the bottom. Solutions like new activation functions, residual connections, or forget gates in LSTMs helped address that.

Quantum Machine Learning is still in the ‘scientific playground’ phase.

But quantum barren plateaus are far worse. It’s like being dropped in the middle of the Sahara and told there’s a hole one meter wide and 10 km deep somewhere nearby (the optimal solution). The terrain is flat, and no matter how much you feel around with your foot or look around, you have no idea whether the hole is 1 km or 1,000 km away. The algorithm gets lost in the vastness of Hilbert space and stops learning.

So, if current quantum hardware (NISQ) is noisy and limited, and classical computers are robust but blind to certain correlations, why choose just one?

Quantum Boosting: combining classical and quantum to enhance learning

One of the most promising and pragmatic paths is using ensemble techniques. In classical ML, we know that combining several ‘weak’ models (as in Random Forests) reduces variance and improves generalization. The idea is to create a heterogeneous ‘committee of experts’, and this has benefits. For example, error orthogonality: ensemble theory says that combining models works better when their errors are uncorrelated.

Say you train a powerful classical model that achieves, say, 85% accuracy. You then take the remaining 15% of misclassified cases (the residuals). Now you train a small quantum model specifically to tackle those residuals.

Because this quantum model focuses on a data subset with 'hard' structures, its usefulness is maximized without having to load the entire dataset into the QPU. This is known as Quantum Boosting, using the quantum kernel only where its dimensional advantage truly matters.

Combining models works better when their errors are uncorrelated.

Conclusion: optimism or realism?

Quantum Machine Learning isn’t just ‘faster ML’, but a paradigm shift. We might never use quantum computers to classify cat photos or predict ad clicks (classical ML already excels at that), but if we’re still figuring out what LLMs are capable of, any forecast about quantum computing’s future is bold, to say the least.

Where QML will certainly prove valuable is in the QQ quadrant: discovering new materials, developing drugs, or unlocking fundamental physics, problems that are inherently quantum. That’s where QML plays at home. As Richard Feynman said at the end of his famous 1981 lecture: “Nature isn’t classical, dammit. And if you want to make a simulation of nature, you’d better make it quantum.” For everything else, we’re still searching for that elusive algorithm that proves encoding our classical world into atoms is worth the effort.

Quantum Machine Learning isn’t just ‘faster ML’, it’s a paradigm shift.

References:

- What is Quantum Machine Learning (QML)? | by Be Tech! with Santander | Medium

- Overview | IBM Quantum Learning

- Understanding quantum computing’s most troubling problem—the barren plateau

Hybrid Cloud

Hybrid Cloud Cyber Security & NaaS

Cyber Security & NaaS AI & Data

AI & Data IoT & Connectivity

IoT & Connectivity Business Applications

Business Applications Intelligent Workplace

Intelligent Workplace Consulting & Professional Services

Consulting & Professional Services Small Medium Enterprise

Small Medium Enterprise Health and Social Care

Health and Social Care Industry

Industry Retail

Retail Tourism and Leisure

Tourism and Leisure Transport & Logistics

Transport & Logistics Energy & Utilities

Energy & Utilities Banking and Finance

Banking and Finance Smart Cities

Smart Cities Public Sector

Public Sector